Should Markets Be Free?

Both theory and reality tell us that purely free markets don't make much sense, but free market concepts are still useful within common-sense regulatory frameworks

Regardless of whether a political debate pertains to health care, gun control, climate change, drug reform, consumer protection, or taxes, the degree to which government should be involved is often a contentious issue. It is often assumed (either implicitly or explicitly) by one side of the debate that less or no government involvement is better, usually based upon the economic theories surrounding free markets. But does it really make sense to hold such assumptions before delving into the details of a debate? Clearly, the answer is no, based upon economic theory and reality.

What is a Free Market, and Why Have One?

To begin, let’s clarify what we mean when using the term “free market”. In the context of this article, a free market refers to an economic system in which no government regulation exists, such that markets dictate how societies function. In other words, the forces of supply and demand alone shape all aspects of our society. This means that no government restrictions over the production and consumption of goods and services exist. The term is used more loosely in other contexts, but for illustrative purpose we will use this strict definition.

So, why should we have a free market? Generally speaking, proponents reason that the free market is the most effective system to create prosperity and improve the living standards of society. But how do free markets do this, what are the underlying assumptions, and are these assumptions realistic?

The Mechanics and Assumptions Behind Free Markets

How exactly do free markets benefit society, in theory? The answer is found by examining the basic economic concept of supply and demand. In theory, prices for goods and services will settle at the point where the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied for a given good or service, referred to as the equilibrium price. When prices are at equilibria, markets are deemed to be functioning efficiently, indicating that resources are allocated based on the needs and wants of society. There are no shortages or oversupplies, and waste is minimized. However, when governments interfere in markets, it may be impossible to reach those optimal prices. This is interpreted to mean that less government regulation translates into a more efficient economic system, leading to greater prosperity in the long-run.

Despite being theoretical, political ideologies are shaped by these ideas. But let's take a closer look at a few key assumptions:

Assumption 1: Markets are perfectly competitive

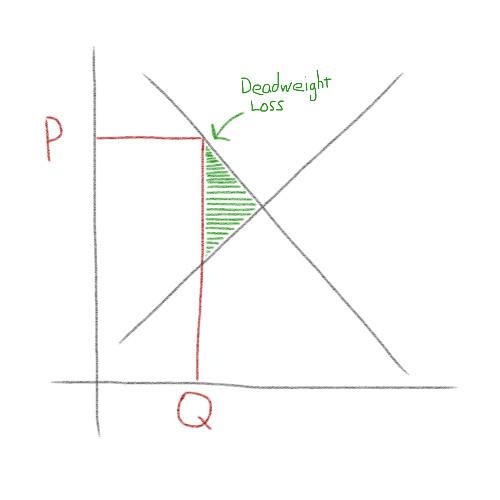

The concepts described thus far apply only to markets that are perfectly competitive. But most markets are not perfectly competitive. The markets for monopolies, oligopolies, and monopolistic competition function differently. Companies with pricing power may find it more profitable to produce less-than-optimal quantities at higher-than-optimal prices, resulting in deadweight loss to society. In theory, to mitigate or reduce these inefficiencies, governments can regulate markets through price controls, antitrust legislation, and other measures. In doing so, producers are forced to price goods and services closer to equilibrium prices. Therefore, theory indicates that regulation can actually help make markets more efficient.

In markets that are not competitive, less-than-optimal quantities are sold at higher-than-optimal prices, leading to deadweight loss.

Assumption 2: All market participants are fully informed and rational

In order for resources to be allocated optimally, it is assumed that all participants know everything and make the best decisions possible. However, as we know from experience, humans are irrational and not fully informed, which means that we are susceptible to making poor decisions. And the consequences of irrationality can be enormous. For example, the bursting of economic bubbles (created by asset mispricings) can cause widespread damage to economies, as occurred during the Great Recession in 2008. Or for example, high levels of anthropogenic carbon emissions have not been adequately factored into prices of goods and services (another bubble), contributing to potentially irreversible damage to the environment. The fact that humans are imperfect is crucial, because it implies that existing prices may not reflect the true needs and wants of society, and that our collective resources are not being allocated efficiently. Moreover, this assumption ignores the reality of information asymmetries which give certain market participants the upper hand relative to others.

Assumption 3: The factors of production are freely mobile

In order for markets to function efficiently, the factors of production - that is, capital and labor - are able to freely move through economic systems and between production processes. The basic idea is that the appropriate factors should be accessible to producers in markets at best prices. In practical terms, this would mean (among other things) that no immigration restrictions would exist to prevent laborers from entering to markets to work, and that capital would also able to move between markets with no restrictions. In reality, many countries have stringent policies in place which restrict the movement and use of labor and capital (for better or worse).

Overall, purely free market systems may indeed work to maximize economic efficiency, but only under highly specific theoretical (i.e. unrealistic) circumstances. As such, we should be critical of blanket generalizations stating that less government is best, without considering the specifics.

Regulation Can Be Beneficial

To illustrate how regulation can be beneficial, let’s look at a few basic examples (both theoretical and real-world).

Life in a purely free market

Imagine living in a purely free market society (that is, an anarcho-capitalist society). All markets are completely unregulated, and no governments exist to interfere with these markets (i.e. there are no laws). In such a society, it would be up to individuals to hire private police forces to enforce personal security and property rights. Individuals would have to pave and maintain their own roads, and they would have to transact with others in order to use their roads. Since an agency like the FDA would not exist, it would be up to individuals to test products for harmful substances. No laws would exist to regulate contentious goods and services, like narcotics, prostitution, abortion, assassination, etc. Deceptive marketing tactics would not be controlled. It is quite clear that life under these circumstances would be chaotic and highly inefficient. It seems that such a system would eventually lead to the coordination, regulation, and standardization of activities among individuals - that is, the formation of government.

The idea that regulation is necessary to maintain functioning markets is, unsurprisingly, supported by thought leaders in economics. Notably, Nobel laureate Robert Shiller cogently explained importance of regulation in a 2015 New York Times column.

Financial markets

Absent regulation, financial market insiders may exploit information asymmetries to achieve financial gains at the expense of others. Executives of publicly traded companies could artificially inflate stock prices by providing false financial information to the public (the Enron scandal is a classic example). Brokerage firms could forego fiduciary duties by selling risky securities unsuitable to clients for the sake of profit. The presence of financial regulation helps prevent prices from being distorted, and ensures fairness among participants.

Slavery

The market for forced labor is prohibited by governments because slavery is now viewed as immoral, as it should be. Of course, this has not always been the case historically. Slavery was abolished only 15 decades ago in the US, and it has only recently been criminalized in some countries, highlighting the fact that regulations are not established exclusively for the purposes of economic efficiency, but rather are reflections of collective moral standards.

Regulation Can Be Harmful

Thus far, we have discussed the downsides of unconstrained free markets, but there are clearly legitimate upsides to leveraging free market mechanisms. Let's outline a few scenarios in which excessive regulation can cause (or has caused) problems.

Planned Economies

On the opposite end of the spectrum, imagine a society in which government controls everything, setting prices and output for all goods and services. History has shown us that governments are unable to control all aspects of markets and have them function effectively; markets are simply too complex. A government, which is run by a small subset of society, does not and cannot fully know and administer to all the needs, wants, and values of an entire society. Inevitably, this system would lead to asset mispricings, an inefficient allocation of resources, and ultimately a poorly functioning society. This supports the idea that free market mechanisms (that is, price determination by market participants) do have a vital role to play in economies, but - critically - within the context of reasonable regulatory frameworks.

Narcotics

The production, sale, and consumption of narcotics is prohibited in many countries around the world. With respect to the United States, some argue that the War on Drugs, which was initiated by the Nixon administration and continues today, has failed, and that action must be taken to approach the issue differently. In its first report in 2011, the Global Commission on Drug Policy argued that prohibition and criminalization should be replaced with new models of legalization (i.e. less regulation, but not complete deregulation). The Commission has since issued numerous reports supporting its argument.

Tariffs

In 2018, the Trump administration enacted tariffs on certain imports, which is causing countries to enact retaliatory tariffs on the US. Tariffs are recognized to be counterproductive regulatory tools, as they result in suboptimal prices and output (again resulting in deadweight loss). According to a Reuters poll of economists in early 2018, the vast majority believed that the tariffs risked doing more harm than good and could spark a wider trade war (which it did). Bloomberg’s examination of corporate earnings reports in July 2018 (subsequently updated in October 2018) indicates that the majority of corporations examined were adversely impacted by tariffs (notably, the CEO of Ford said that the tariffs cost the company approximately $1 billion). More recently, a December 2018 Bloomberg report shows that US companies paid over $1 billion in tariffs on technology products alone in a single month.

How Should Markets Be Regulated?

As is evident, a truly free market is a bad idea, as is the opposite. But where on the spectrum between completely free markets and completely unfree markets should economies lie? It is impossible to point to a certain location on that spectrum and declare that it is the optimal balance. Attempting to do so would be naïve at best, and disingenuous at worst. Rather than assuming it a starting point to policy debates, that balance should be the result of examining the nature of the relevant markets and crafting regulations to help those markets function optimally. In certain markets, it might make sense to take a laissez-faire approach, perhaps only requiring that fraud and deception are disallowed, but nothing more. In other markets, it might make sense for governments to directly control prices and/or output.

Once this idea is accepted, more important questions arise: What is “best” or “optimal” for a society, and what is a “fair” game in economics? It is clear that not all regulations are created equal. Effective and ineffective regulations exist, and some regulations (or the lack of regulations) favor one group in society over another. Given the fact that economies are immensely complex and societal values fluctuate, it is not surprising that considerable disagreement exists with respect to the best policy decisions to make. Nevertheless, efforts should be made to understand markets; understand the wants, needs, and values of societies; and regulate with those understandings in mind. In that way, governments do what’s best for the people they serve. But for starters, it must be clear that the belief that unfettered free markets are desirable, and that government is not useful as a technology for improving livelihoods, ignores both theory and reality.